Thomas Cole's "View of Schroon Mountain"

Essay written by John Sasso (Historian and Founder of "History and Legends of the Adirondacks" Facebook Group)

===========================================

Undoubtedly, one of the most well-known and celebrated landscape paintings of the Adirondacks is Thomas Cole’s “View of Schroon Mountain, Essex Co., New York, After a Storm.” Painted in 1838 by Cole in his studio in Catskill, New York (now the Thomas Cole National Historic Site), the subject of the painting appears as a sharp, lofty peak in the background, whose prominence parts the storm clouds to let the sun shine upon the hills whose forests are bursting in the colors of Fall. The peak known then as Schroon Mountain, is today’s Hoffman Mountain. The focus of this essay is what drew Cole to eventually create this beautiful piece of work and the location he ventured to in the Schroon region to sketch the view he would transcribe to oil and canvas.

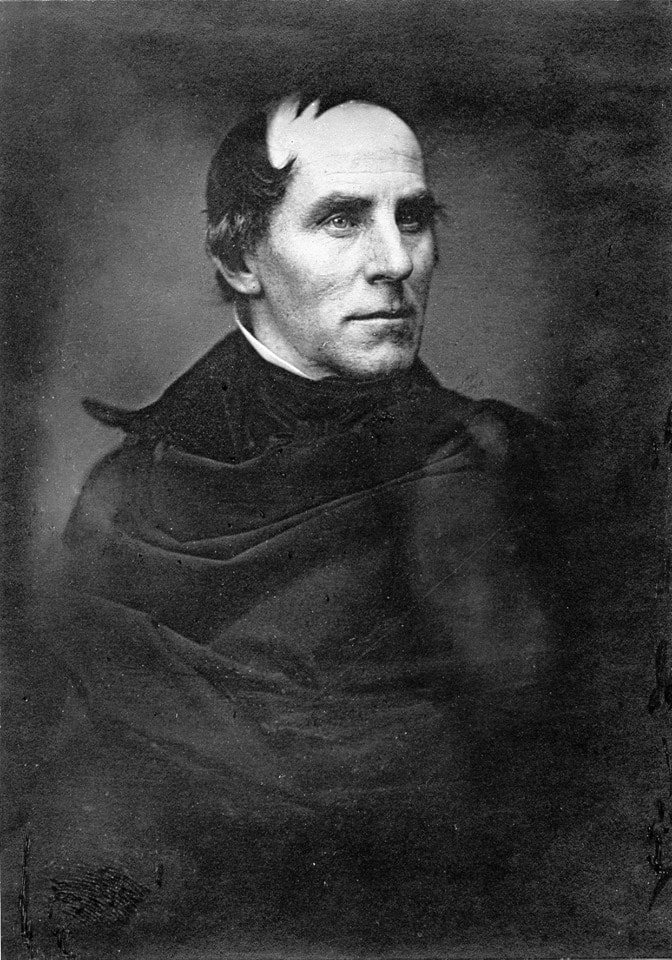

Thomas Cole (1801-1848), English-born artist and poet, is considered the founder of the Hudson River School, an informal group of mid-nineteenth century landscape artists who drew inspiration from European Romanticism and whose works celebrated the natural beauty of the American landscape. The Hudson River School is the first school of American landscape painting, whose era spanned from 1825 to 1875. Although the name implies a geographic focus on the Hudson River Valley of New York State, the members of the school did not adhere to such a constraint, as their works included regions of New England, the American West, and South America. Artists of the school produced works which emphasized the peaceful coexistence of man with nature, at times including an agricultural setting in their paintings. Man was viewed as having stewardship over nature. This sentiment is conveyed by Cole in his influential “Essay on American Scenery” (“American Monthly Magazine, Jan. 1836):

“It is a subject that to every American ought to be of surpassing interest; for, whether he beholds the Hudson mingling waters with the Atlantic--explores the central wilds of this vast continent, or stands on the margin of the distant Oregon, he is still in the midst of American scenery--it is his own land; its beauty, its magnificence, its sublimity--all are his; and how undeserving of such a birthright, if he can turn towards it an unobserving eye, an unaffected heart!”

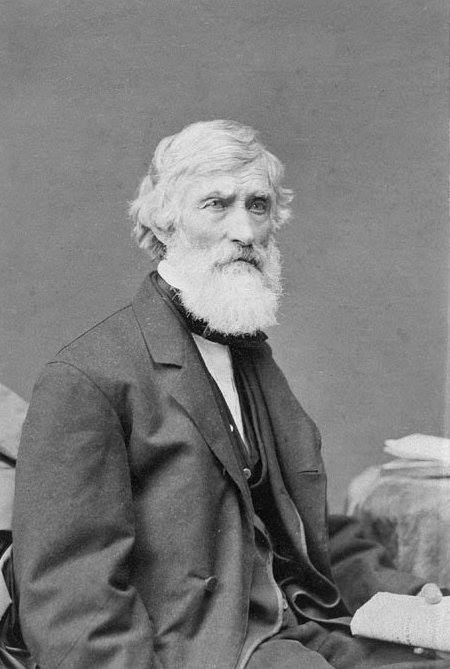

The school would include other famous artists such as Asher Durand, Frederic Church, Sanford Gifford, Jasper Cropsey, and Thomas Doughty; artists such as Durand, Church, and Doughty, would include Adirondack landscapes in their works. For more information on the Hudson River School, see https://www.theartstory.org/movement-hudson-river-school.htm.

Cole’s first artistic excursion into the Adirondacks was in 1826, when he traveled north, paying visits to Glens Falls, Fort Edward, Fort William Henry, Lake George, and Fort Ticonderoga. During that time, he visited William Ferris Pell, who built the Pavilion at Fort Ticonderoga as his summer home that same year and made sketches for his painting “Gelyna: A View near Ticonderoga”; Cole would modify the painting in 1829 to coincide with his friend Giulian C. Verplanck’s story “Gelyna: A Tale of Albany and Ticonderoga Seventy Years Ago.” In August of 1826, Baltimore art patron Robert Gilmor, Jr. wrote to Cole, suggesting that he create a painting with “some known subject from Cooper’s novels to enliven the landscape.” Gilmor was referring to James Fenimore Cooper’s classic novel “The Last of the Mohicans,” which was published that year. From 1826 to 1827, Cole produced four exhibition paintings based on “The Last of the Mohicans”: “Landscape with Figures: A Scene from ‘The Last of the Mohicans’” (1826), “Scene from ‘The Last of the Mohicans,’ Cora Kneeling at the Feet of Tamenund” (1827), “Landscape Scene from ‘The Last of the Mohicans’" (1827), and “Landscape Scene from ‘The Last of the Mohicans,’ The Death of Cora” (1827). Although the setting for “The Last of the Mohicans” was set in Lake George, the landscape in Cole’s two versions of “Cora Kneeling at the Feet of Tamenund” were inspired from his trip to the White Mountains of New Hampshire in the summer of 1827; the mountain prominent in the painting is Corroway Peak, and the lake is Winipisioge Lake. In 1830, Cole was commissioned by John Howard Hinton to produce seven paintings of views in the United States, from which engravings would be made for Hinton’s popular, two-volume classic “The History and Topography of the United States” (1830 and 1832). Of the engravings, they included a scene of sailboats on Lake George, a raft made of timber on Lake Champlain, and the ruins of Fort Ticonderoga; the following are links to the engravings:

https://adirondack.pastperfectonline.com/…/CE4DDF95-85C2-4B…

https://adirondack.pastperfectonline.com/…/59380FA5-099A-40…

https://adirondack.pastperfectonline.com/…/F1B5A48F-919F-4D…

Beginning in the autumn of 1835, Cole made several excursions into the Schroon Lake region. The reflections of these trips to Schroon Lake, the Catskills, and other regions, in Cole’s own words, are given in Louis Legrand Noble’s following works: “The Course of Empire, Voyage of Life, and Other Pictures of Thomas Cole, N.A.” (1853) and “The Life and Works of Thomas Cole, N.A.” (1856). In a diary entry dated October 7, 1835, Cole writes about how he was rowing on Schroon Lake and noted that the view from the lake was “exceedingly fine.” He continues:

“On both hands, from shores of sand and pebbles, gently rise the thickly-wooded hills: before you miles of blue water stretch away: in the distance mountains of remarkable beauty bound the vision. Two summits in particular attracted my attention: one of a serrated outline, and the other like a lofty pyramid. At the time I saw them, they stood in the midst of the wilderness like peaks of sapphire. It is my intention to visit this region at a more favourable season.”

The “lofty pyramid” he was likely referring to is Hoffman Mountain, which clearly captured his attention. Cole would return to Schroon Lake on June 22, 1837 with his wife, Maria, and the artist Asher Brown Durand and his wife, Mary. Cole recounts this summer trip and how he and Asher ventured to a high point to capture, in pencil sketches, the view of “Schroon Mountain,” which would be the inspiration for Cole’s famous painting – and the subject of this essay – in his diary entry dated July 8, 1837. It is Cole who would introduce Durand to the Schroon Lake region, which inspired Durand produce several landscape paintings and sketches such as “A View of Schroon Lake” (1849) and “Adirondacks” (1848). Of the beauty of the landscape of the Adirondacks, Cole wrote, “I do not remember to have seen in Italy a composition of mountains so beautiful or pictorial as this glorious range of the Adirondack.”

In late June of 1837, Cole and Durand ventured off the road about three miles from their lodging, to get a better view of the mountains west of Schroon Lake for their sketch-work. According to Ann Breen Metcalfe in her article “Tales of Hoffman: The Rise and Fall of an Adirondack Outpost” (“Adirondack Life,” March/April 2011), this was the house of a Van Benthuysen. It appears that Cole’s ulterior motive was to get an exceptional view of Hoffman Mountain, to be included in an eventual work of art, for he writes:

“We climbed a steep hill, on which many sheep were at pasture, and gained a magnificent view. Below us lay a little lake, embosomed in the hills, and a perfect mirror of the surrounding woods: beyond were hills, partially cleared, and beyond these Schroon Mountain, raising its peak into the sky. Here we sketched.”

From a pencil sketch from Cole’s sketch-book entitled “Schroon Mountain - from near the head of Schroon Lake,” dated June 30, 1837 (for full, zomable sketch, see: https://www.dia.org/…/schroon-mountain-near-head-schroon-la…), a computer-based analysis of the sketch (coupled with Cole’s diary entry and other evidence) has led me to believe that the steep hill Cole referred to is today’s Severance Hill, a small peak located almost four miles southeast of Hoffman Mountain. The little lake Cole refers to is the small, unnamed body of water lying between Jones Hill and Severance Hill. I will delve into the analysis of this sketch later on.

Beyond the pond, below the point where Cole and Durand sketched, they saw some hills cleared of timber (likely due to lumbering activity in the area) which they hoped would provide a much better view of Hoffman Mountain. Tempted by such a prospect, they quickly descended the hill they were on towards the pond, went around its shores and through a swampy forest, and came to a clearing upon which there were one or two log cabins. Cole observed how the few residents were surprised to see two strangers dash across their land while saying nary a word. Continuing to their destination, unabated, Cole writes:

“We climbed the topmost knoll of the clearing, trampling down the luxuriant clover, and, beneath some giant denizens of the woods, whose companions had all laid low, we eagerly looked towards the west, and – were disappointed. A mass of wood on the declivity of the hill enviously hid the anticipated prospect. For once I wished the axe had not stayed. But we were not to be foiled easily. We entered the wood, and found it by a narrow strip. We emerged and our eyes were blessed. There was no lake-view as we had expected, but the hoary mountain rose in silent grandeur, its dark head clad in a sense forest of evergreens, cleaving the sky, ‘a star-y pointed pyramid.’ Below, stretched to the mountain’s base a mighty mass of forest, unbroken but by the rising and sinking of the earth on which it stood. Here we felt the sublimity of untamed wildness, and the majesty of the eternal mountains.”

From the clearing on this hill, the location of which I have determined to be the most likely point where Cole and Durand stood awe-struck by the panorama before them, they commenced sketches of their “grandest view.” Cole’s description of Hoffman Mountain as a (quoted) “star-y point pyramid” is in reference to a verse in John Milton’s “Epitaph to Shakespeare.” The sketch Cole produced is entitled “View of Schroon Mountain – Looking North,” dated June 28, 1837 (for full, zoomable sketch, see:https://www.dia.org/…/view-schroon-mountain-looking-north-j…). Although sketched in the summer, Cole took some artistic liberties with the landscape when creating his painting, such as portraying the region of Hoffman Mountain in the height of the autumn season and making the mountain higher and more sharply pointed than it actually is. The careful, scrutinizing eye will also note two Native Americans towards the bottom-center of the painting: both in a red-feather head-dress, looking at one another, with the one on the left wearing a dark-blue garment and pointing towards the east.

To the extent I am aware, no study has been made of where Cole was when he made the aforementioned sketch. To this end, I leveraged two free pieces of mapping software available to the public: web-based caltopo.com, and Google Earth Pro. The former has a feature called “View From Here,” which allows one to view the topography of the surrounding area from where they are situated on a map, as if they were standing at that point. The latter has a similar feature called “Street View,” which is often used in the web-based Google Maps to allow one to view what their surroundings would be like if they were driving on a particular road. I have successfully used both pieces of software before to analyze a c.1890 Seneca Ray Stoddard photograph and Asher Durand’s 1848 painting “Adirondacks.”

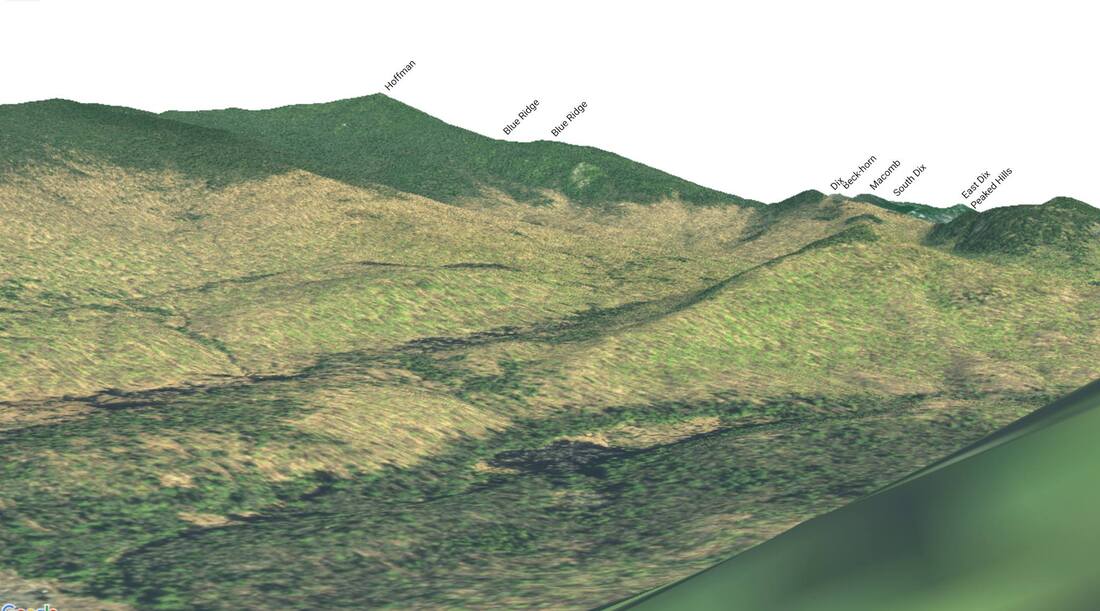

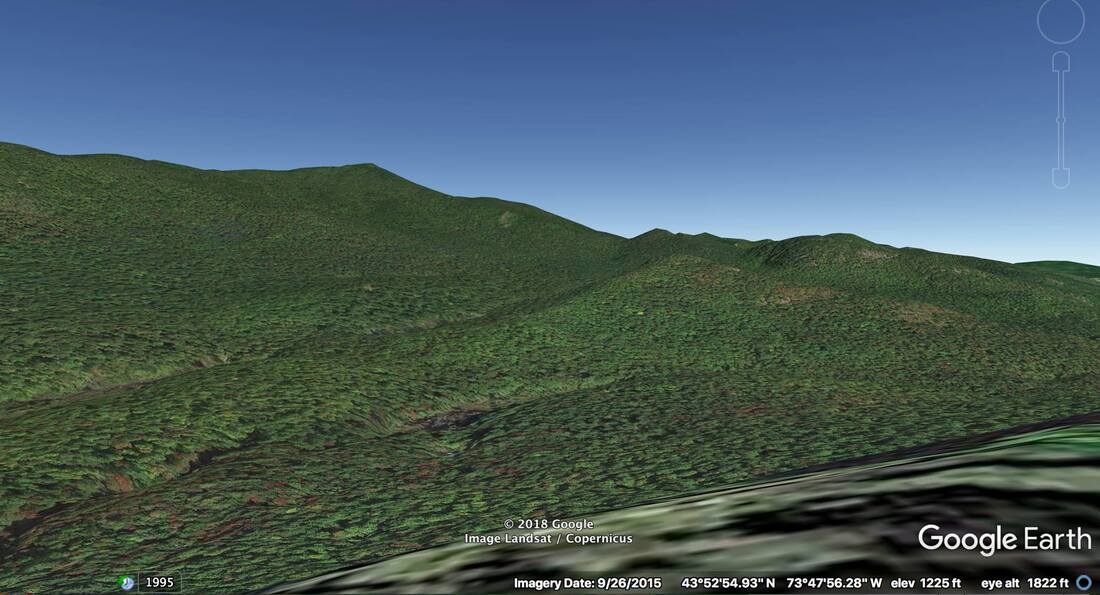

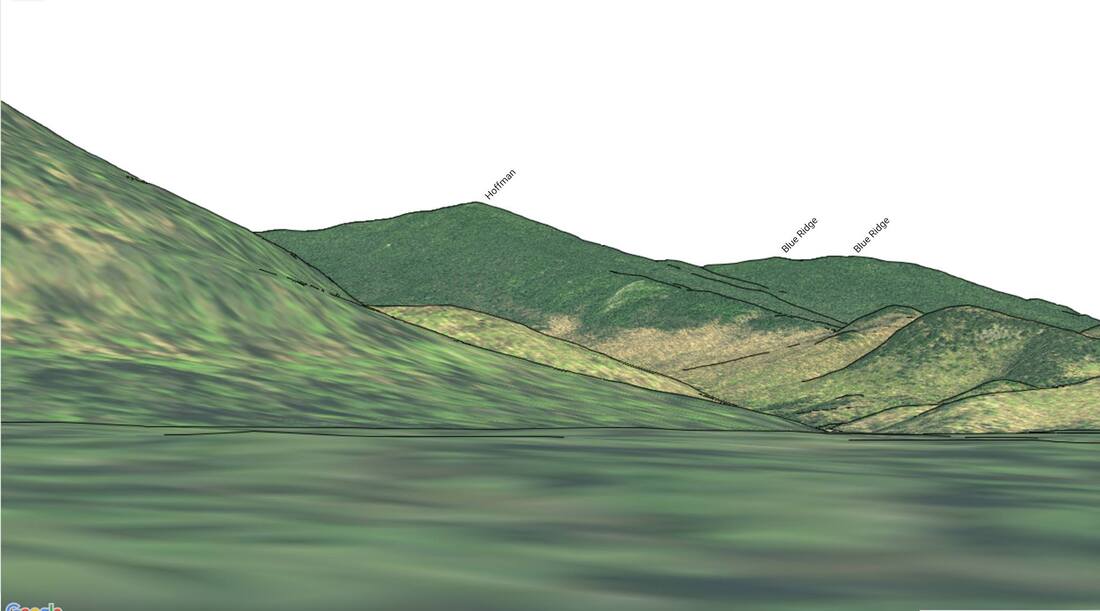

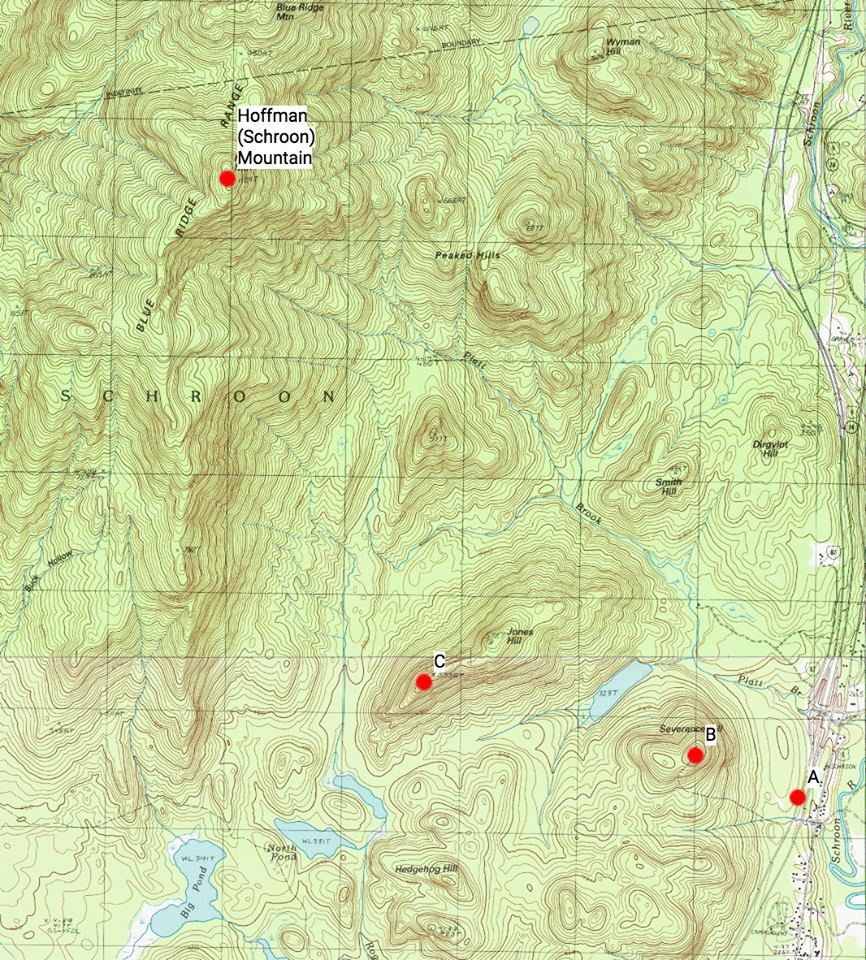

Knowing what was being viewed (Hoffman Mountain) and Cole’s diary entry giving some idea of his direction of travel (towards the west, from Schroon Lake) helped in focusing on what region of the map to look. Although a thorough discussion of the methodology I employed is beyond the scope of this essay, the first step in my analysis was to draw out what I call a Region of Likelihood (ROL), which encompasses where the landscape scene was likely sketched from, based on the profile of Hoffman Mountain. Next, given that Cole wrote he and Durand were on a high point when they stopped to make their sketch, I employed the “View From Here” feature on high points such as Severance Hill, Hedgehog Hill, Jones Hill, as well as those that are not named. In particular, I focused on those near a body of water, since Cole said they went past a pond en route to their final destination. After much panning, zooming, and examination of views from various points, I arrived at a point with the best match to Cole’s sketch: off the western slope of the southwest hump of Jones Hill, or coordinates (43.8731,-73.7962). The snapshot of the view from this point in caltopo.com is provided, with the surrounding peaks annotated. As in Cole’s sketch and painting, we see the southern ridge of Hoffman Mountain to the left, rising towards the summit; Blue Ridge Mountain behind the eastern slope of Hoffman Mountain, which merges with the Peaked Hills; just to the east and behind the Peaked Hills, Dix Peak and Macomb Mountain peeking out on the far right; as the painting depicts, the marsh between Jones Hill and the southern ridge of Hoffman Mountain.

Returning to my suspicion that Cole and Durand may have ventured up Severance Hill before arriving on Jones Hill during their sketching expedition, one reason which led to this is a sketch of Cole’s entitled “Schroon Mountain – from near the head of Schroon Lake,” dated June 30, 1837, just two days after he made the sketch of Hoffman Mountain from Jones Hill. The sketch depicts a pasture with a fence across the slope and a figure of a farmer tending to his land. Recall that Cole and Durand came across farmland on their way up the first steep hill. Performing a similar analysis on the sketch with caltopo.com as before, the location (43.8643,-73.7567), which is along the Northway (I-87) on the eastern base of Severance Hill, provided an excellent match; see the snapshot of the view at that location in caltopo.com. The rising slope in the foreground, to the left of Hoffman Mountain, is the northeast slope of Severance Hill. From Cole’s July 8, 1837 diary entry, he mentions wanting a better view of the mountains to the west from off the road. The view of Hoffman Mountain rising above the hills in grand stature, as shown in Cole’s sketch, would not surprisingly entice Cole and Durand to venture off further for a prize view. Had they viewed Hoffman Mountain from one of the hills south of Jones Hill, then they would have ventured northward.

It would be negligent of me to neglect mentioning a poem which Cole wrote as an ode to Hoffman Mountain, entitled “Song of a Spirit.” The tone of the poem is one where the mountain is a great, lonesome spirit speaking about itself, how it is able to rejoice after withstanding the terrible forces of Nature over many millennia. The first four verses of this poem are:

"An awful privilege it is to wear a spirit’s form,

And solitary live for aye on this vast mountain peak;

To watch, afar beneath my feet, the darkly-heaving storm,

And see its cloudy billows o’er the craggy ramparts break;"

The American author and poet Arthur Billings Street appears to have been well aware of Cole’s poem, for in his classic 1869 work on the Adirondacks, “The Indian Pass,” Street writes:

“thence struck in a northeasterly direction a rough road, ascending widely cleared heights, whence lay a broad forest landscape, with Schroon Mountain – the Spirit Mountain of the red man – lifting its dial-top grandly at the south, and then through twining woods.”

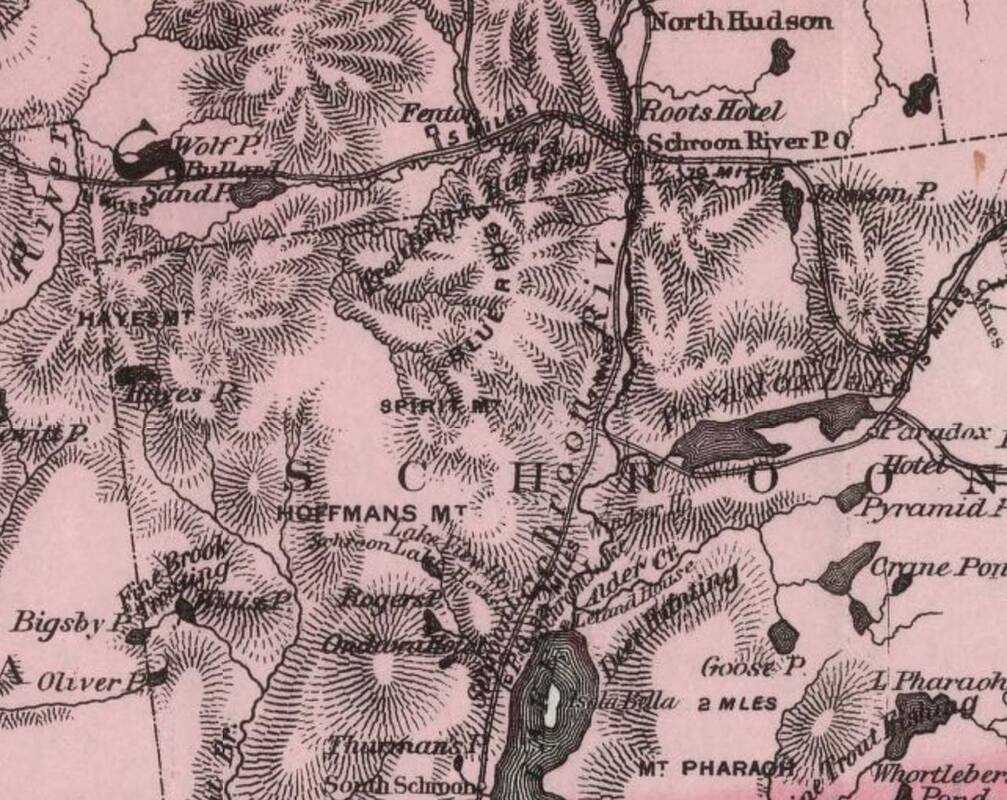

“SPIRIT MT” made its appearance in the 1872 edition of W.W. Ely’s “Map of the New York Wilderness,” where it appears between “HOFFMANS MT” and “BLUE RIDGE.” When E.R. Wallace published his version of Ely’s map in 1882, entitled “Map of the New York Wilderness and the Adirondacks,” he kept Spirit Mountain on it. It appears that the map-makers may have been mistaken and thought Spirit Mountain was another peak near Hoffman Mountain, hence, their placement of it on their map. I have been unable to find any survey for a Spirit Mountain in the region, and the origin of this alias for Hoffman Mountain appears to lie with Mr. Street.

In closing, it has once again been demonstrated how public-domain mapping software can be used to analyze the landscape of historic paintings, sketches, photographs, and other illustrations. Although requiring some trial-and-error effort, out-of-the-box thinking, and (sometimes) access to historical documents relevant to what is being analyzed, such software can be used to determine what is being viewed and where the artist/photographer may have been when they captured the scene. A significant benefit of the software is that it may often preclude the need to perform a visit to possible locations in the field, which can be time-consuming, costly, and arduous. It is my hope that this type of landscape analysis for historical purposes will gain interest, and to someday collaborate with professionals in the field of art to study this effort further.

Essay written by John Sasso (Historian and Founder of "History and Legends of the Adirondacks" Facebook Group)

===========================================

Undoubtedly, one of the most well-known and celebrated landscape paintings of the Adirondacks is Thomas Cole’s “View of Schroon Mountain, Essex Co., New York, After a Storm.” Painted in 1838 by Cole in his studio in Catskill, New York (now the Thomas Cole National Historic Site), the subject of the painting appears as a sharp, lofty peak in the background, whose prominence parts the storm clouds to let the sun shine upon the hills whose forests are bursting in the colors of Fall. The peak known then as Schroon Mountain, is today’s Hoffman Mountain. The focus of this essay is what drew Cole to eventually create this beautiful piece of work and the location he ventured to in the Schroon region to sketch the view he would transcribe to oil and canvas.

Thomas Cole (1801-1848), English-born artist and poet, is considered the founder of the Hudson River School, an informal group of mid-nineteenth century landscape artists who drew inspiration from European Romanticism and whose works celebrated the natural beauty of the American landscape. The Hudson River School is the first school of American landscape painting, whose era spanned from 1825 to 1875. Although the name implies a geographic focus on the Hudson River Valley of New York State, the members of the school did not adhere to such a constraint, as their works included regions of New England, the American West, and South America. Artists of the school produced works which emphasized the peaceful coexistence of man with nature, at times including an agricultural setting in their paintings. Man was viewed as having stewardship over nature. This sentiment is conveyed by Cole in his influential “Essay on American Scenery” (“American Monthly Magazine, Jan. 1836):

“It is a subject that to every American ought to be of surpassing interest; for, whether he beholds the Hudson mingling waters with the Atlantic--explores the central wilds of this vast continent, or stands on the margin of the distant Oregon, he is still in the midst of American scenery--it is his own land; its beauty, its magnificence, its sublimity--all are his; and how undeserving of such a birthright, if he can turn towards it an unobserving eye, an unaffected heart!”

The school would include other famous artists such as Asher Durand, Frederic Church, Sanford Gifford, Jasper Cropsey, and Thomas Doughty; artists such as Durand, Church, and Doughty, would include Adirondack landscapes in their works. For more information on the Hudson River School, see https://www.theartstory.org/movement-hudson-river-school.htm.

Cole’s first artistic excursion into the Adirondacks was in 1826, when he traveled north, paying visits to Glens Falls, Fort Edward, Fort William Henry, Lake George, and Fort Ticonderoga. During that time, he visited William Ferris Pell, who built the Pavilion at Fort Ticonderoga as his summer home that same year and made sketches for his painting “Gelyna: A View near Ticonderoga”; Cole would modify the painting in 1829 to coincide with his friend Giulian C. Verplanck’s story “Gelyna: A Tale of Albany and Ticonderoga Seventy Years Ago.” In August of 1826, Baltimore art patron Robert Gilmor, Jr. wrote to Cole, suggesting that he create a painting with “some known subject from Cooper’s novels to enliven the landscape.” Gilmor was referring to James Fenimore Cooper’s classic novel “The Last of the Mohicans,” which was published that year. From 1826 to 1827, Cole produced four exhibition paintings based on “The Last of the Mohicans”: “Landscape with Figures: A Scene from ‘The Last of the Mohicans’” (1826), “Scene from ‘The Last of the Mohicans,’ Cora Kneeling at the Feet of Tamenund” (1827), “Landscape Scene from ‘The Last of the Mohicans’" (1827), and “Landscape Scene from ‘The Last of the Mohicans,’ The Death of Cora” (1827). Although the setting for “The Last of the Mohicans” was set in Lake George, the landscape in Cole’s two versions of “Cora Kneeling at the Feet of Tamenund” were inspired from his trip to the White Mountains of New Hampshire in the summer of 1827; the mountain prominent in the painting is Corroway Peak, and the lake is Winipisioge Lake. In 1830, Cole was commissioned by John Howard Hinton to produce seven paintings of views in the United States, from which engravings would be made for Hinton’s popular, two-volume classic “The History and Topography of the United States” (1830 and 1832). Of the engravings, they included a scene of sailboats on Lake George, a raft made of timber on Lake Champlain, and the ruins of Fort Ticonderoga; the following are links to the engravings:

https://adirondack.pastperfectonline.com/…/CE4DDF95-85C2-4B…

https://adirondack.pastperfectonline.com/…/59380FA5-099A-40…

https://adirondack.pastperfectonline.com/…/F1B5A48F-919F-4D…

Beginning in the autumn of 1835, Cole made several excursions into the Schroon Lake region. The reflections of these trips to Schroon Lake, the Catskills, and other regions, in Cole’s own words, are given in Louis Legrand Noble’s following works: “The Course of Empire, Voyage of Life, and Other Pictures of Thomas Cole, N.A.” (1853) and “The Life and Works of Thomas Cole, N.A.” (1856). In a diary entry dated October 7, 1835, Cole writes about how he was rowing on Schroon Lake and noted that the view from the lake was “exceedingly fine.” He continues:

“On both hands, from shores of sand and pebbles, gently rise the thickly-wooded hills: before you miles of blue water stretch away: in the distance mountains of remarkable beauty bound the vision. Two summits in particular attracted my attention: one of a serrated outline, and the other like a lofty pyramid. At the time I saw them, they stood in the midst of the wilderness like peaks of sapphire. It is my intention to visit this region at a more favourable season.”

The “lofty pyramid” he was likely referring to is Hoffman Mountain, which clearly captured his attention. Cole would return to Schroon Lake on June 22, 1837 with his wife, Maria, and the artist Asher Brown Durand and his wife, Mary. Cole recounts this summer trip and how he and Asher ventured to a high point to capture, in pencil sketches, the view of “Schroon Mountain,” which would be the inspiration for Cole’s famous painting – and the subject of this essay – in his diary entry dated July 8, 1837. It is Cole who would introduce Durand to the Schroon Lake region, which inspired Durand produce several landscape paintings and sketches such as “A View of Schroon Lake” (1849) and “Adirondacks” (1848). Of the beauty of the landscape of the Adirondacks, Cole wrote, “I do not remember to have seen in Italy a composition of mountains so beautiful or pictorial as this glorious range of the Adirondack.”

In late June of 1837, Cole and Durand ventured off the road about three miles from their lodging, to get a better view of the mountains west of Schroon Lake for their sketch-work. According to Ann Breen Metcalfe in her article “Tales of Hoffman: The Rise and Fall of an Adirondack Outpost” (“Adirondack Life,” March/April 2011), this was the house of a Van Benthuysen. It appears that Cole’s ulterior motive was to get an exceptional view of Hoffman Mountain, to be included in an eventual work of art, for he writes:

“We climbed a steep hill, on which many sheep were at pasture, and gained a magnificent view. Below us lay a little lake, embosomed in the hills, and a perfect mirror of the surrounding woods: beyond were hills, partially cleared, and beyond these Schroon Mountain, raising its peak into the sky. Here we sketched.”

From a pencil sketch from Cole’s sketch-book entitled “Schroon Mountain - from near the head of Schroon Lake,” dated June 30, 1837 (for full, zomable sketch, see: https://www.dia.org/…/schroon-mountain-near-head-schroon-la…), a computer-based analysis of the sketch (coupled with Cole’s diary entry and other evidence) has led me to believe that the steep hill Cole referred to is today’s Severance Hill, a small peak located almost four miles southeast of Hoffman Mountain. The little lake Cole refers to is the small, unnamed body of water lying between Jones Hill and Severance Hill. I will delve into the analysis of this sketch later on.

Beyond the pond, below the point where Cole and Durand sketched, they saw some hills cleared of timber (likely due to lumbering activity in the area) which they hoped would provide a much better view of Hoffman Mountain. Tempted by such a prospect, they quickly descended the hill they were on towards the pond, went around its shores and through a swampy forest, and came to a clearing upon which there were one or two log cabins. Cole observed how the few residents were surprised to see two strangers dash across their land while saying nary a word. Continuing to their destination, unabated, Cole writes:

“We climbed the topmost knoll of the clearing, trampling down the luxuriant clover, and, beneath some giant denizens of the woods, whose companions had all laid low, we eagerly looked towards the west, and – were disappointed. A mass of wood on the declivity of the hill enviously hid the anticipated prospect. For once I wished the axe had not stayed. But we were not to be foiled easily. We entered the wood, and found it by a narrow strip. We emerged and our eyes were blessed. There was no lake-view as we had expected, but the hoary mountain rose in silent grandeur, its dark head clad in a sense forest of evergreens, cleaving the sky, ‘a star-y pointed pyramid.’ Below, stretched to the mountain’s base a mighty mass of forest, unbroken but by the rising and sinking of the earth on which it stood. Here we felt the sublimity of untamed wildness, and the majesty of the eternal mountains.”

From the clearing on this hill, the location of which I have determined to be the most likely point where Cole and Durand stood awe-struck by the panorama before them, they commenced sketches of their “grandest view.” Cole’s description of Hoffman Mountain as a (quoted) “star-y point pyramid” is in reference to a verse in John Milton’s “Epitaph to Shakespeare.” The sketch Cole produced is entitled “View of Schroon Mountain – Looking North,” dated June 28, 1837 (for full, zoomable sketch, see:https://www.dia.org/…/view-schroon-mountain-looking-north-j…). Although sketched in the summer, Cole took some artistic liberties with the landscape when creating his painting, such as portraying the region of Hoffman Mountain in the height of the autumn season and making the mountain higher and more sharply pointed than it actually is. The careful, scrutinizing eye will also note two Native Americans towards the bottom-center of the painting: both in a red-feather head-dress, looking at one another, with the one on the left wearing a dark-blue garment and pointing towards the east.

To the extent I am aware, no study has been made of where Cole was when he made the aforementioned sketch. To this end, I leveraged two free pieces of mapping software available to the public: web-based caltopo.com, and Google Earth Pro. The former has a feature called “View From Here,” which allows one to view the topography of the surrounding area from where they are situated on a map, as if they were standing at that point. The latter has a similar feature called “Street View,” which is often used in the web-based Google Maps to allow one to view what their surroundings would be like if they were driving on a particular road. I have successfully used both pieces of software before to analyze a c.1890 Seneca Ray Stoddard photograph and Asher Durand’s 1848 painting “Adirondacks.”

Knowing what was being viewed (Hoffman Mountain) and Cole’s diary entry giving some idea of his direction of travel (towards the west, from Schroon Lake) helped in focusing on what region of the map to look. Although a thorough discussion of the methodology I employed is beyond the scope of this essay, the first step in my analysis was to draw out what I call a Region of Likelihood (ROL), which encompasses where the landscape scene was likely sketched from, based on the profile of Hoffman Mountain. Next, given that Cole wrote he and Durand were on a high point when they stopped to make their sketch, I employed the “View From Here” feature on high points such as Severance Hill, Hedgehog Hill, Jones Hill, as well as those that are not named. In particular, I focused on those near a body of water, since Cole said they went past a pond en route to their final destination. After much panning, zooming, and examination of views from various points, I arrived at a point with the best match to Cole’s sketch: off the western slope of the southwest hump of Jones Hill, or coordinates (43.8731,-73.7962). The snapshot of the view from this point in caltopo.com is provided, with the surrounding peaks annotated. As in Cole’s sketch and painting, we see the southern ridge of Hoffman Mountain to the left, rising towards the summit; Blue Ridge Mountain behind the eastern slope of Hoffman Mountain, which merges with the Peaked Hills; just to the east and behind the Peaked Hills, Dix Peak and Macomb Mountain peeking out on the far right; as the painting depicts, the marsh between Jones Hill and the southern ridge of Hoffman Mountain.

Returning to my suspicion that Cole and Durand may have ventured up Severance Hill before arriving on Jones Hill during their sketching expedition, one reason which led to this is a sketch of Cole’s entitled “Schroon Mountain – from near the head of Schroon Lake,” dated June 30, 1837, just two days after he made the sketch of Hoffman Mountain from Jones Hill. The sketch depicts a pasture with a fence across the slope and a figure of a farmer tending to his land. Recall that Cole and Durand came across farmland on their way up the first steep hill. Performing a similar analysis on the sketch with caltopo.com as before, the location (43.8643,-73.7567), which is along the Northway (I-87) on the eastern base of Severance Hill, provided an excellent match; see the snapshot of the view at that location in caltopo.com. The rising slope in the foreground, to the left of Hoffman Mountain, is the northeast slope of Severance Hill. From Cole’s July 8, 1837 diary entry, he mentions wanting a better view of the mountains to the west from off the road. The view of Hoffman Mountain rising above the hills in grand stature, as shown in Cole’s sketch, would not surprisingly entice Cole and Durand to venture off further for a prize view. Had they viewed Hoffman Mountain from one of the hills south of Jones Hill, then they would have ventured northward.

It would be negligent of me to neglect mentioning a poem which Cole wrote as an ode to Hoffman Mountain, entitled “Song of a Spirit.” The tone of the poem is one where the mountain is a great, lonesome spirit speaking about itself, how it is able to rejoice after withstanding the terrible forces of Nature over many millennia. The first four verses of this poem are:

"An awful privilege it is to wear a spirit’s form,

And solitary live for aye on this vast mountain peak;

To watch, afar beneath my feet, the darkly-heaving storm,

And see its cloudy billows o’er the craggy ramparts break;"

The American author and poet Arthur Billings Street appears to have been well aware of Cole’s poem, for in his classic 1869 work on the Adirondacks, “The Indian Pass,” Street writes:

“thence struck in a northeasterly direction a rough road, ascending widely cleared heights, whence lay a broad forest landscape, with Schroon Mountain – the Spirit Mountain of the red man – lifting its dial-top grandly at the south, and then through twining woods.”

“SPIRIT MT” made its appearance in the 1872 edition of W.W. Ely’s “Map of the New York Wilderness,” where it appears between “HOFFMANS MT” and “BLUE RIDGE.” When E.R. Wallace published his version of Ely’s map in 1882, entitled “Map of the New York Wilderness and the Adirondacks,” he kept Spirit Mountain on it. It appears that the map-makers may have been mistaken and thought Spirit Mountain was another peak near Hoffman Mountain, hence, their placement of it on their map. I have been unable to find any survey for a Spirit Mountain in the region, and the origin of this alias for Hoffman Mountain appears to lie with Mr. Street.

In closing, it has once again been demonstrated how public-domain mapping software can be used to analyze the landscape of historic paintings, sketches, photographs, and other illustrations. Although requiring some trial-and-error effort, out-of-the-box thinking, and (sometimes) access to historical documents relevant to what is being analyzed, such software can be used to determine what is being viewed and where the artist/photographer may have been when they captured the scene. A significant benefit of the software is that it may often preclude the need to perform a visit to possible locations in the field, which can be time-consuming, costly, and arduous. It is my hope that this type of landscape analysis for historical purposes will gain interest, and to someday collaborate with professionals in the field of art to study this effort further.

Above Image: Thomas Cole’s “View of Schroon Mountain, Essex Co., New York, After a Storm” (1838)

(Source: The Cleveland Museum of Art)

(Source: The Cleveland Museum of Art)

Above Photo: Thomas Cole (1801-1848) (Source: Wikipedia)

Above Photo: Asher Brown Durand (1796-1886) (Source: Wikipedia)

Above Image: Thomas Cole’s “Gelyna: A View near Ticonderoga” (1826) (Source: Wikipedia Commons)

Above Image: Thomas Cole’s Scene from ‘The Last of the Mohicans,’ Cora Kneeling at the Feet of Tamenund” (1827) (Source: Wikipedia Commons)

Above Image: Thomas Cole’s “‘The Last of the Mohicans’: The Death of Cora” (1827) (Source: Wikipedia Commons)

Above Photo: Result of “View From Here” in caltopo.com on the southwest knob of Jones Hill, which best matches Thomas Cole’s sketch “View of Schroon Mountain – Looking North”

Above Photo: Result of Street View in Google Earth Pro on the southwest knob of Jones Hill, which best matches Thomas Cole’s sketch “View of Schroon Mountain – Looking North”

Above Photo: Result of “View From Here” in caltopo.com from the eastern foot of Severance Hill, which best matches Thomas Cole’s sketch “Schroon Mountain - from near the head of Schroon Lake”

Above Photo: Photo of Hoffman Mountain from Jones Hill

Above Image:

Locations A, B, and C in caltopo.com, where “View From Here” was used:

A: The eastern foot of Severance Hill

B: Summit of Severance Hill (not matched against any sketch)

C: Southwestern knob of Jones HillAbove Photo:

Locations A, B, and C in caltopo.com, where “View From Here” was used:

A: The eastern foot of Severance Hill

B: Summit of Severance Hill (not matched against any sketch)

C: Southwestern knob of Jones HillAbove Photo:

Image Above: Portion of W.W. Ely’s 1879 edition of “Map of the New York Wilderness.” Spirit Mountain is denoted between Hoffman Mountain and Blue Ridge.

(Source: David Rumsey Map Collection)

(Source: David Rumsey Map Collection)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed