Adirondack history is filled with strange connections. The largest private landowner in Schroon Lake history is linked to Warren Harding’s German spy mistress and to Pale Male, the famous hawk whose aerie in New York City overlooks Central Park.

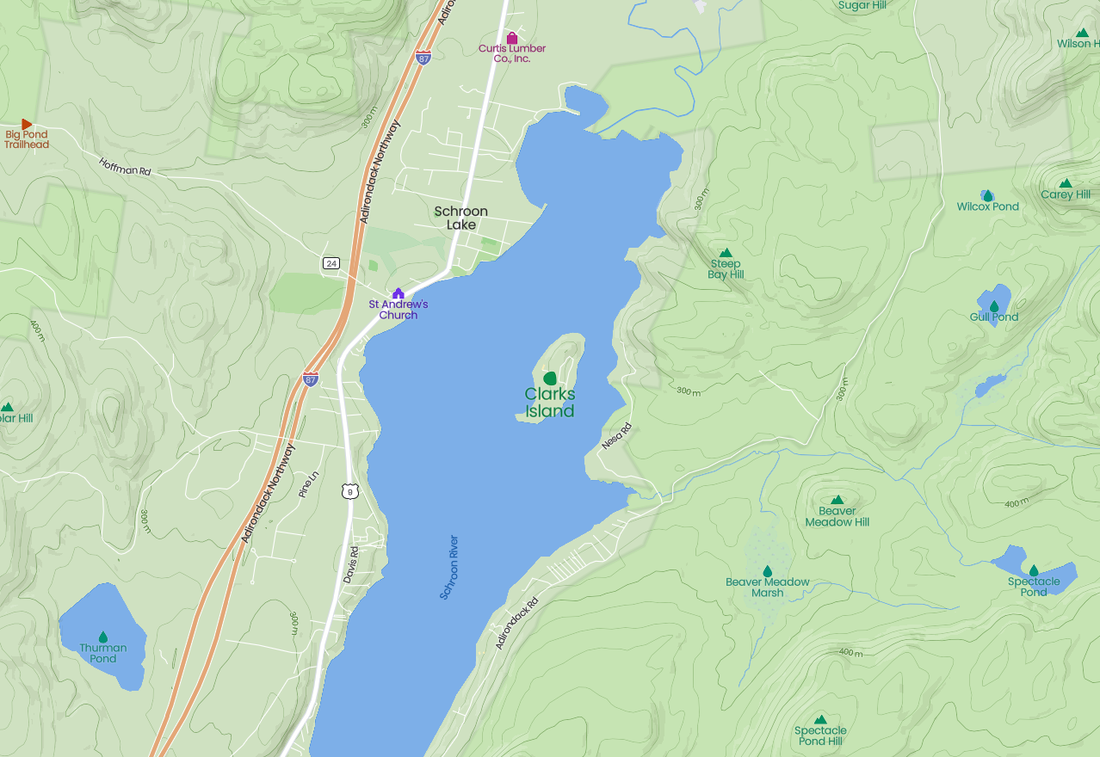

Wilhelm Pickhardt (1834 -1895) once owned all the land on Schroon’s east shore from the head of the lake down to Starbuckville. He planned to combine Schroon and Paradox Lakes to create a super lake that would give tourists a thrilling trip from Lake George to Lake Champlain.

Pickhardt, who made his fortune manufacturing dyes, brought his family to Schroon Lake in the early 1870’s as guests at the fashionable Leland House hotel. He fell in love with the Adirondacks, which reminded him of his native Bavaria. First, he bought the Stock Farm north of the village where today’s Schroon Lake Marina is located, including the race track whose remains are still visible. Partnering with Thurman Leland of the hotel family, Pickhardt bred trotter racehorses. He named the property the Millbrook Stock Farm for the stream that runs through the hamlet of Adirondack to Schroon Lake.

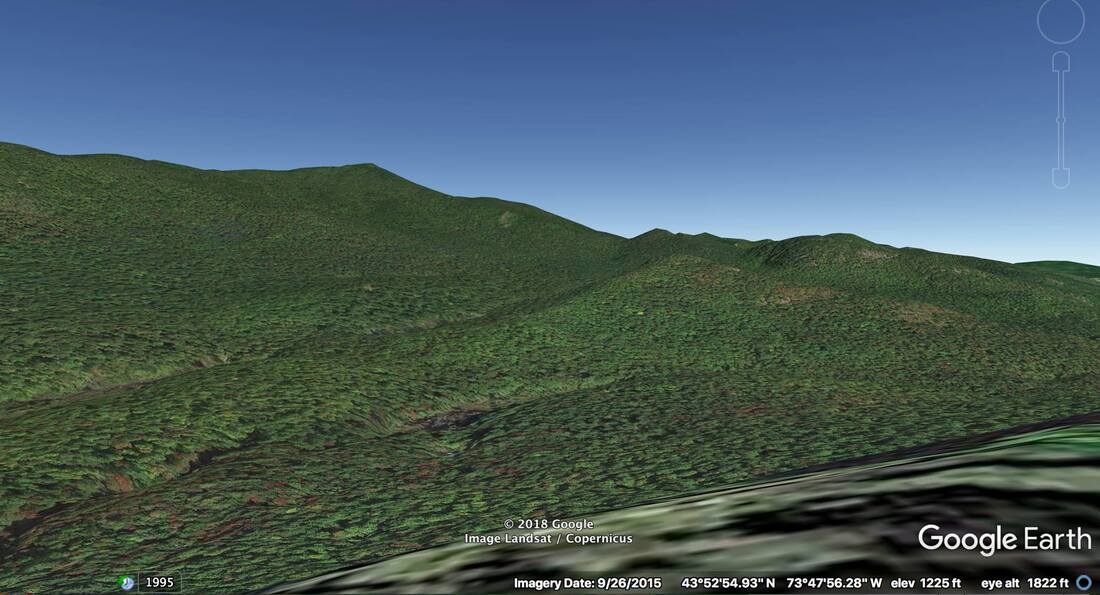

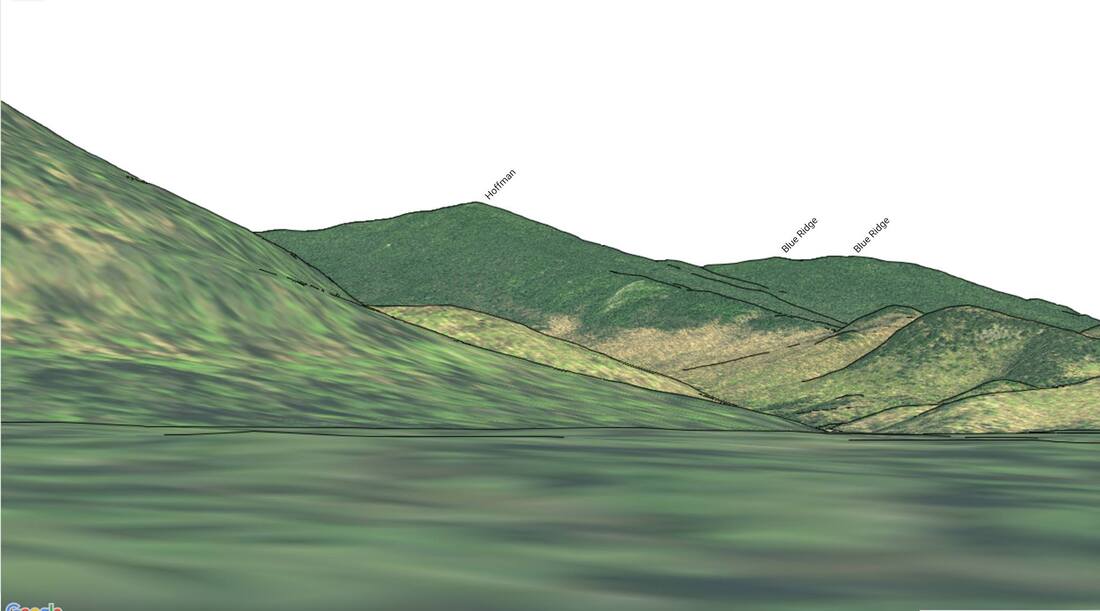

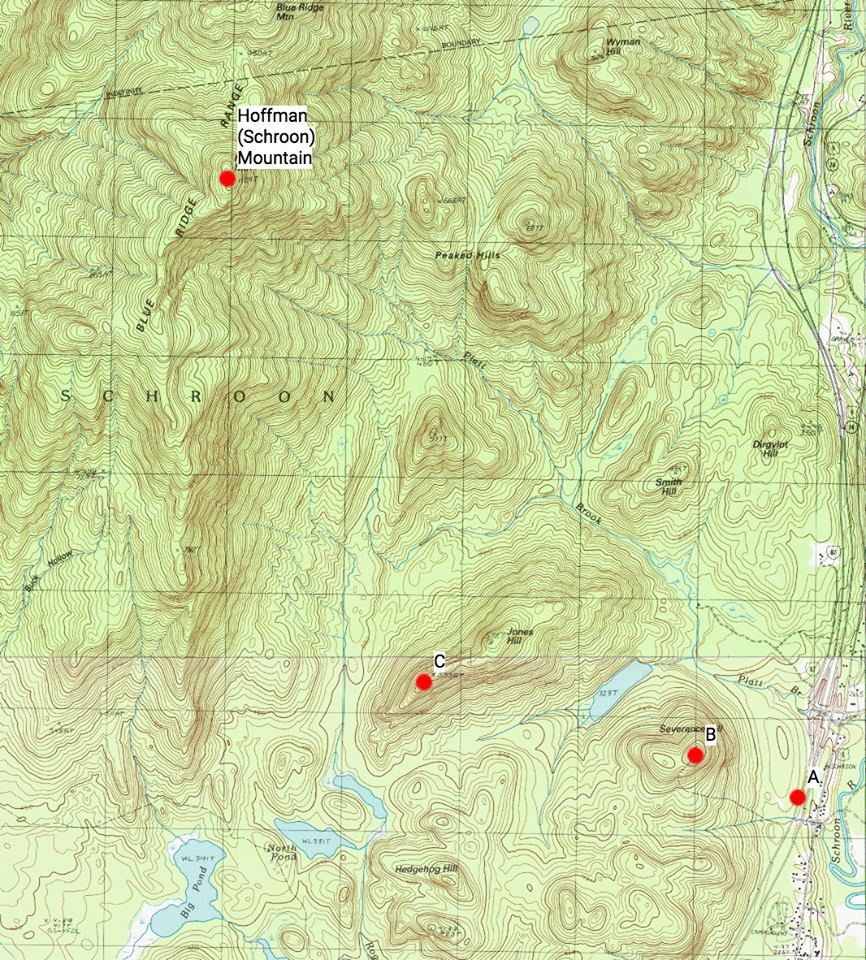

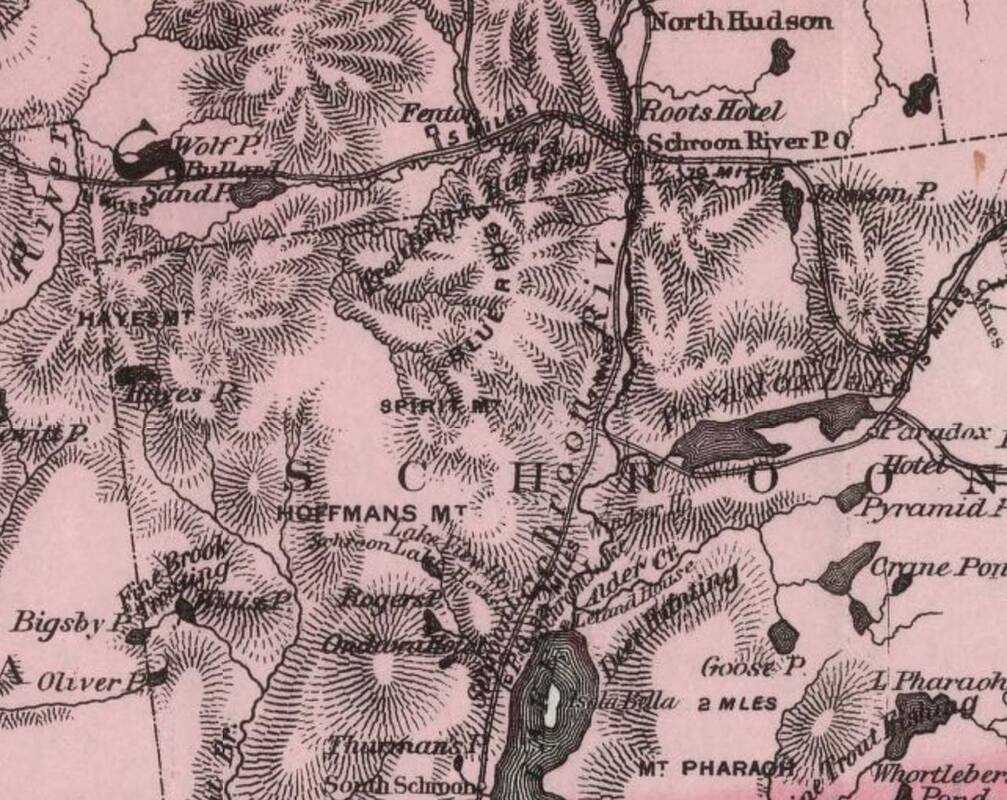

Then in the 1880s and early 1890s Pickhardt purchased, one tract at a time, the entire east shore of Schroon Lake and much of the Schroon River. That means he owned all the land from Lockwood Bay and the Schroon Lake Marina at the head of the lake south through Adirondack hamlet, thence to the foot of the lake and down the Schroon River to Starbuckville north of Chestertown. His holdings extended deep into the woods; in northern Warren County he owned all of Mill Brook from the lake back to its source in Pharaoh Lake. And he owned the lost hamlet of Gregoryville on the old road between Adirondack hamlet and Crane Pond. In all, he bought 25,000 acres in Essex and Warren Counties, a tract some 13 miles long and, in some places, 5 miles deep.

In 1862 Pickhardt married Beresford Strong, from an aristocratic British family. They had five children, Sydney, Adrian, Ione, Julian and Emile. The family spent summers in Schroon Lake, first at the Leland House and later at their own home north of the village. Beresford Pickhardt became a leader of Schroon’s summer social set, and entertained at teas and concerts in her home.

Pickhardt and Kutrof in New York City imported dye stuffs, colors and chemicals. In 1878 the firm became the American agent for the Badische Aniline & Soda Fabrik, a German corporation and the largest producer of aniline dyes in Europe. Pickhardt also tried his hand at inventing, obtaining patents for various household devices.

Wilhelm Pickhardt (1834 -1895) once owned all the land on Schroon’s east shore from the head of the lake down to Starbuckville. He planned to combine Schroon and Paradox Lakes to create a super lake that would give tourists a thrilling trip from Lake George to Lake Champlain.

Pickhardt, who made his fortune manufacturing dyes, brought his family to Schroon Lake in the early 1870’s as guests at the fashionable Leland House hotel. He fell in love with the Adirondacks, which reminded him of his native Bavaria. First, he bought the Stock Farm north of the village where today’s Schroon Lake Marina is located, including the race track whose remains are still visible. Partnering with Thurman Leland of the hotel family, Pickhardt bred trotter racehorses. He named the property the Millbrook Stock Farm for the stream that runs through the hamlet of Adirondack to Schroon Lake.

Then in the 1880s and early 1890s Pickhardt purchased, one tract at a time, the entire east shore of Schroon Lake and much of the Schroon River. That means he owned all the land from Lockwood Bay and the Schroon Lake Marina at the head of the lake south through Adirondack hamlet, thence to the foot of the lake and down the Schroon River to Starbuckville north of Chestertown. His holdings extended deep into the woods; in northern Warren County he owned all of Mill Brook from the lake back to its source in Pharaoh Lake. And he owned the lost hamlet of Gregoryville on the old road between Adirondack hamlet and Crane Pond. In all, he bought 25,000 acres in Essex and Warren Counties, a tract some 13 miles long and, in some places, 5 miles deep.

In 1862 Pickhardt married Beresford Strong, from an aristocratic British family. They had five children, Sydney, Adrian, Ione, Julian and Emile. The family spent summers in Schroon Lake, first at the Leland House and later at their own home north of the village. Beresford Pickhardt became a leader of Schroon’s summer social set, and entertained at teas and concerts in her home.

Pickhardt and Kutrof in New York City imported dye stuffs, colors and chemicals. In 1878 the firm became the American agent for the Badische Aniline & Soda Fabrik, a German corporation and the largest producer of aniline dyes in Europe. Pickhardt also tried his hand at inventing, obtaining patents for various household devices.

BASF plant in Ludwigshafen, 1881 (Wikipedia)

The Pickhardt family’s life in New York City was grand and eccentric. In 1880 Wilhelm bought land on Fifth Avenue at 74th Street, and set out to build an elegant mansion. He hired the noted architect Henry G. Harrison to design his new home. But the resulting structure was not a success. Pickhardt changed the design many times, even as the mansion was being built. Fifteen years after construction began the four-story Renaissance Revival building was completed, but Pickhardt remained dissatisfied.

The Pickhardts never lived in the mansion, nor did anyone else. The $50,000 organ was never played; the furniture never used. Ultimately the mansion was torn down, and a 20-story apartment building was constructed in 1917. The structure, called 927 Fifth Avenue, is a home to millionaires. It gained notoriety in the 1990’s when a red-tailed hawk named Pale Male built its nest on a balcony facing Central Park. The building’s management destroyed the nest but the fury of bird watchers in the park forced them to restore its “cradle.” Red-tailed hawks continue to nest there.

The Pickhardts never lived in the mansion, nor did anyone else. The $50,000 organ was never played; the furniture never used. Ultimately the mansion was torn down, and a 20-story apartment building was constructed in 1917. The structure, called 927 Fifth Avenue, is a home to millionaires. It gained notoriety in the 1990’s when a red-tailed hawk named Pale Male built its nest on a balcony facing Central Park. The building’s management destroyed the nest but the fury of bird watchers in the park forced them to restore its “cradle.” Red-tailed hawks continue to nest there.

Pickardts Mansion called 927 Fifth Avenue aka Pickardts Folly (daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com)

Pale Male in Central Park circa 2011. Or was it? Photo: Francois Portmann (www.audubon.org)

Pale Male in Central Park circa 2011. Or was it? Photo: Francois Portmann (www.audubon.org)

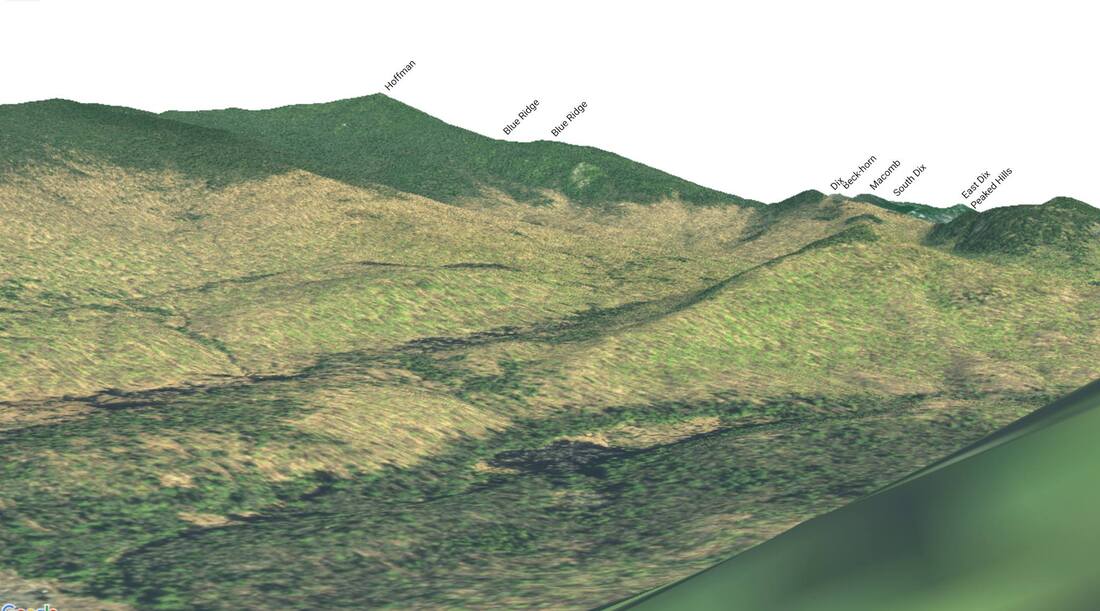

Pickhardt’s goal for the southeast Adirondacks was to create a scenic water route that would take tourists from Lake George to Lake Champlain. This would require building an enormous dam at Starbuckville with the aim of making the Schroon River navigable and raising the water level of Schroon and Paradox Lakes by four feet to create one large body of water. The two lakes are almost the same level, and the paradox occurs in the Spring when the creek that connects them swells up with overflow from the Schroon River, and the water is pushed backwards into Paradox Lake.

The plan was for tourists to take a narrow-gauge railroad from Lake George to Starbuckville. There they would board a steamboat to make the 28-mile trip up the Schroon River and Schroon Lake, on to the east end of the former Paradox Lake, and thence go by rail to Crown Point on Lake Champlain.

The New York Times, in reporting the proposal in 1883, wrote that Pickhardt had already “greatly improved Schroon Village.” He had no interest in lumbering, but he encouraged the various tanneries that flourished on the shores of his property, including the large one known as “The Pit” in South Horicon. Seneca Ray Stoddard must have missed the Times article because he wrote in his 1889 guidebook: “Almost the entire east shore north of Mill Brook, extending back and including Lake Pharaoh, is owned by William (sic) Pickhardt of New York. His intentions in relation to the estate are known — to himself.”

Interestingly, another effort to dam the Schroon River and raise the level of Schroon and Paradox Lakes occurred in 1910-1916. Severe flooding of the Hudson and the perceived need for cheaper electricity led Glens Falls businessmen to propose a dam at Tumblehead Falls below Chestertown. Schroon’s leaders, with the help of influential summer visitors, stopped the project. Construction of the Sacandaga Dam and Reservoir in 1930 handled the problem of flooding.

The plan was for tourists to take a narrow-gauge railroad from Lake George to Starbuckville. There they would board a steamboat to make the 28-mile trip up the Schroon River and Schroon Lake, on to the east end of the former Paradox Lake, and thence go by rail to Crown Point on Lake Champlain.

The New York Times, in reporting the proposal in 1883, wrote that Pickhardt had already “greatly improved Schroon Village.” He had no interest in lumbering, but he encouraged the various tanneries that flourished on the shores of his property, including the large one known as “The Pit” in South Horicon. Seneca Ray Stoddard must have missed the Times article because he wrote in his 1889 guidebook: “Almost the entire east shore north of Mill Brook, extending back and including Lake Pharaoh, is owned by William (sic) Pickhardt of New York. His intentions in relation to the estate are known — to himself.”

Interestingly, another effort to dam the Schroon River and raise the level of Schroon and Paradox Lakes occurred in 1910-1916. Severe flooding of the Hudson and the perceived need for cheaper electricity led Glens Falls businessmen to propose a dam at Tumblehead Falls below Chestertown. Schroon’s leaders, with the help of influential summer visitors, stopped the project. Construction of the Sacandaga Dam and Reservoir in 1930 handled the problem of flooding.

The current Starbuckville Dam located in Chestertown, NY (Photo: Courtesy Diane Cordell) (www.schroonlaker.com)

Up until the 1960’s, old timers around Schroon Lake still called the land on the east shore of the Narrows

“Pickhardt’s Point.” That’s where Pickhardt planned to build a castle and breed a new form of Adirondack deer. Having been raised in the Bavarian town of Berghausen in Germany and, inspired by the enormous Berghausen Castle, Pickhardt sought to have a grand Adirondack home on Schroon Lake. The castle would be on a hill facing west. His steamboat, the Wilhelmina, would be docked at the shore. A large game park, stocked with deer, would surround the site.

Pickhardt was a fervent believer in the popular Aclimitisation movement of the day, which sought to improve animal species by introducing non-native stock. To that end he imported female deer from Germany to be mated with Adirondack bucks, with the idea that the does would become acclimated, and the stock would be enriched. Pickhardt also imported a herd of boars from Germany and planted oak trees to produce acorns for the boars to eat. Without fencing the boars became part of the landscape and ultimately provided dinners for local families.

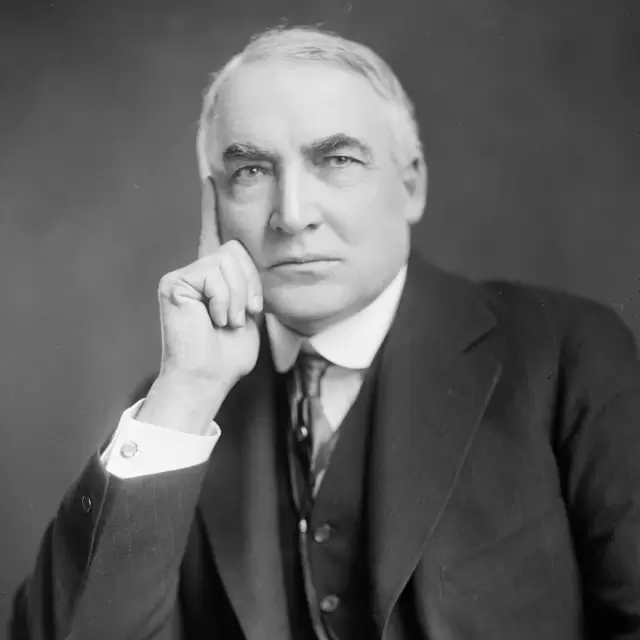

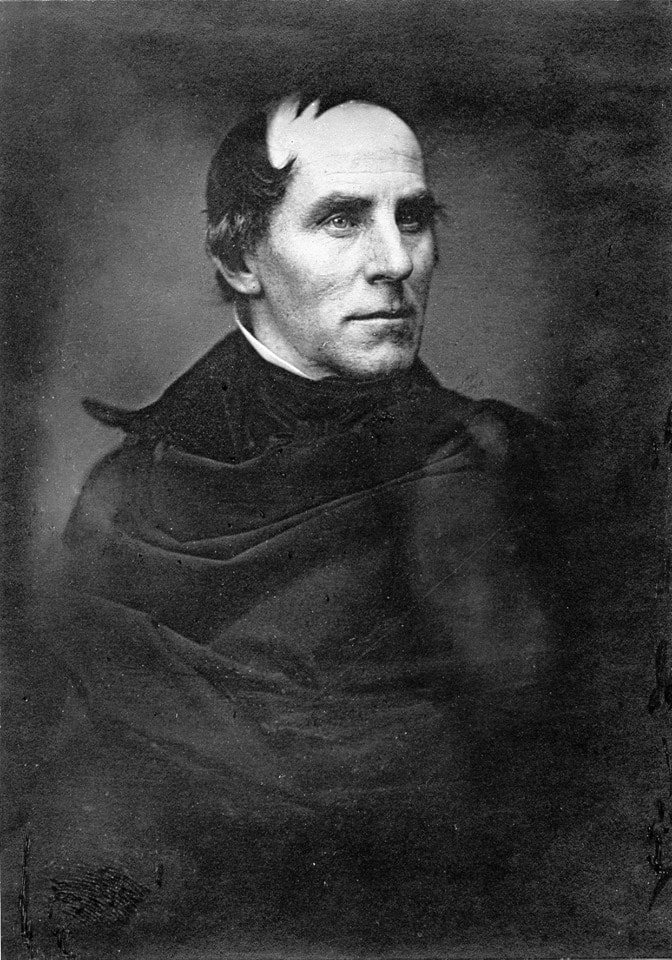

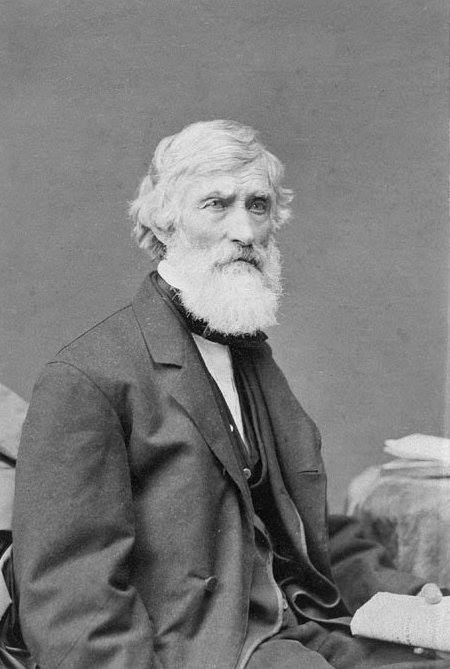

Wilhelm Pickhardt died in 1895 on a trip from Berghausen to Baden. He did not live to witness the disgrace of his daughter Ione, who was accused of spying on the United States. World War I (1914-1918) presented difficulties for some German Americans who were ambivalent about US participation in a war against Germany. In the Midwest many German Americans worked actively for the German cause. One such group was in Marion, Ohio, where Warren Harding lived. Harding was to become the 29th president of the United States, serving only two years until his death in 1923. Loyal to the USA, he seemed unaware that his beloved mistress Carrie Phillips was in a German spy ring. She lived much of the time in Germany, where she served as handler for Ione Pickhardt Zollner, Wilhelm’s daughter.

“Pickhardt’s Point.” That’s where Pickhardt planned to build a castle and breed a new form of Adirondack deer. Having been raised in the Bavarian town of Berghausen in Germany and, inspired by the enormous Berghausen Castle, Pickhardt sought to have a grand Adirondack home on Schroon Lake. The castle would be on a hill facing west. His steamboat, the Wilhelmina, would be docked at the shore. A large game park, stocked with deer, would surround the site.

Pickhardt was a fervent believer in the popular Aclimitisation movement of the day, which sought to improve animal species by introducing non-native stock. To that end he imported female deer from Germany to be mated with Adirondack bucks, with the idea that the does would become acclimated, and the stock would be enriched. Pickhardt also imported a herd of boars from Germany and planted oak trees to produce acorns for the boars to eat. Without fencing the boars became part of the landscape and ultimately provided dinners for local families.

Wilhelm Pickhardt died in 1895 on a trip from Berghausen to Baden. He did not live to witness the disgrace of his daughter Ione, who was accused of spying on the United States. World War I (1914-1918) presented difficulties for some German Americans who were ambivalent about US participation in a war against Germany. In the Midwest many German Americans worked actively for the German cause. One such group was in Marion, Ohio, where Warren Harding lived. Harding was to become the 29th president of the United States, serving only two years until his death in 1923. Loyal to the USA, he seemed unaware that his beloved mistress Carrie Phillips was in a German spy ring. She lived much of the time in Germany, where she served as handler for Ione Pickhardt Zollner, Wilhelm’s daughter.

Warren G. Harding ~ THE 29TH PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES (www.whitehouse.gov)

Ione Pickhardt (1871-1932) was married three times, first to American businessman Charles Warner Shope, second to a German baron named Kurt Loeffelholz von Colberg and third to German merchant Wilhelm Zollner. A handsome, imposing woman, Ione spent her childhood and teenage summers in Schroon Lake. Even before WW I started she was suspected of spying on American military installations, troop movements and materiel. She was arrested in a hotel room in Chattanooga in 1917. She was dressed, but a partially clothed young US Army officer was found hiding under the bed. One of her sons studied at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis; he was forced to leave when authorities accused his mother of passing information about that institution to the Germans. Ione was charged with violating the Espionage Act but never convicted. The national news media made much of her infamy, focusing on her wealth, good looks and reputation for using sex for spying. And in Schroon Lake, the locals were properly shocked by the notoriety of their one-time summer resident.

Iona Shope Wilhelmina Sutton Zollner (above). Her son, Midshipman William Krebs Beresford Shope (below), was forced to resign from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1918 due to "pro-German sympathies." (Library of Congress) www.usni.org

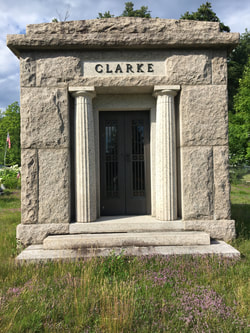

At his death at age 61, Wilhelm Pickhardt was buried in a family tomb in Burghausen. His estate was estimated by New York newspapers to be worth $10 million ($35,000,000 today). The funds were controlled by Beresford Pickhardt, and passed on to the children at her discretion.

Pickhardt’s vast holdings of Adirondack land were affected as the hemlock supply dried up and the tanning industry deteriorated. Businessmen from Glens Falls bought the Pickhardt acres and spent the next decades lumbering the land. Millions of dollars in logs were floated down Schroon Lake and through the Schroon and Hudson Rivers to the mills in Warrensburg and Glens Falls, adding to the fortunes of the region’s lumber barons. As the trees grew back much of the land was acquired by New York State. Seasonal homes were built on privately owned waterfront lots. Dwight Harris built a golf course and clubhouse at Pickhardt’s Point. A new Starbuckville Dam was constructed on the Schroon River in 2005 at a cost of $1.2 million.

After Pickhardt’s death the Stock Farm continued its work. Horses kept on the property and races were managed by George Brown, whose father Lloyd had been Pickhardt’s coach driver. A freed slave, Lloyd served in the US Army during the Civil War and then moved to Schroon Lake. His wife Anna kept a boarding house for Negro servants at the grand hotels. The family are buried in Schroon’s Protestant cemetery. On each Memorial Day local veterans place American flags on the graves of Lloyd Brown and his fellow veterans.

The Pickhardt house remains on the Stock Farm property with Pickhardt Street next to it. In later years Aubrey and Alice Slaterpryce installed a marina, Par-3 golf course and camp ground on the site.

The Pickhardt castle was never built. Pickhardt’s Point at the Narrows became known as Three Bears. Wilhelm Pickhardt’s ambition was boundless, but his dreams remain unfulfilled. And in Springtime the swollen Schroon River continues to create a paradox as it pushes the connecting stream backwards into Paradox Lake.

~ Ann Breen Metcalf, Author

NOTE: To learn more about the Pickhardt Family and their summer life in Schroon Lake, please visit the Schroon North Hudson Historical Society Musem this coming Summer 2023. We will have a new and exciting exhibit that will be on display telling the story of this interesting family and their influence on the history of the Town of Schroon.

Pickhardt’s vast holdings of Adirondack land were affected as the hemlock supply dried up and the tanning industry deteriorated. Businessmen from Glens Falls bought the Pickhardt acres and spent the next decades lumbering the land. Millions of dollars in logs were floated down Schroon Lake and through the Schroon and Hudson Rivers to the mills in Warrensburg and Glens Falls, adding to the fortunes of the region’s lumber barons. As the trees grew back much of the land was acquired by New York State. Seasonal homes were built on privately owned waterfront lots. Dwight Harris built a golf course and clubhouse at Pickhardt’s Point. A new Starbuckville Dam was constructed on the Schroon River in 2005 at a cost of $1.2 million.

After Pickhardt’s death the Stock Farm continued its work. Horses kept on the property and races were managed by George Brown, whose father Lloyd had been Pickhardt’s coach driver. A freed slave, Lloyd served in the US Army during the Civil War and then moved to Schroon Lake. His wife Anna kept a boarding house for Negro servants at the grand hotels. The family are buried in Schroon’s Protestant cemetery. On each Memorial Day local veterans place American flags on the graves of Lloyd Brown and his fellow veterans.

The Pickhardt house remains on the Stock Farm property with Pickhardt Street next to it. In later years Aubrey and Alice Slaterpryce installed a marina, Par-3 golf course and camp ground on the site.

The Pickhardt castle was never built. Pickhardt’s Point at the Narrows became known as Three Bears. Wilhelm Pickhardt’s ambition was boundless, but his dreams remain unfulfilled. And in Springtime the swollen Schroon River continues to create a paradox as it pushes the connecting stream backwards into Paradox Lake.

~ Ann Breen Metcalf, Author

NOTE: To learn more about the Pickhardt Family and their summer life in Schroon Lake, please visit the Schroon North Hudson Historical Society Musem this coming Summer 2023. We will have a new and exciting exhibit that will be on display telling the story of this interesting family and their influence on the history of the Town of Schroon.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed